The Transition: Resistance and the Black Arts Movement

Black women transitioned from being passive subjects of contemptuous representations to becoming radical agents of change, using visual art and activism to seize control over their narratives.

Early Visual Self-Assertion

Long before the Black Feminist Art Movement officially began, Black women used portraiture to take agency over their own bodies and appearances and challenge racist beliefs.

Tintype of an “African American Woman and Child” This early portraiture shows how Black people took portraiture seriously, appearing at photography studios in elegant attire. The mother and child in such images display a confident, middle-class appearance. By presenting themselves in fine clothes, Black women “countered a long history of contemptuous representations” by creating a new form of Black visibility and projecting “black pride and identity”. These images asserted that they deserved to be seen as equal members of society and belonged in America, even when their citizenship was questioned.

The Black Feminist Art Movement: Rejecting the White Lens

By the late 1960s and 1970s, Black women artists began formally establishing their own political and artistic spaces because they recognized that the broader social change movements failed to address their intersectional oppression.

Exclusion from Mainstream Feminism: While the mainstream feminist art movement centered on women’s experiences, “it was often told through a White lens” and ignored the specific experience of existing at the “intersection of a racial and gender identity that has historically been oppressed”.

Intersectionality and Rejection: Black women artists rejected the premise that white, Black, and women of color were similarly oppressed simply based on gender. Instead, they claimed their intersectional identities as central to their artistry and fight for liberation. Their response was to form their own movements and organizations to address both the racism they faced daily and the sexism they experienced from white men and within Black men in the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements.

The Price of Activism: The commitment to intersectional feminism often put these women at odds with the Black establishment. Pioneer Faith Ringgold asserted that in the 1970s, being “black and a feminist was equivalent to being a traitor to the cause of black people,” believing she was dividing the community.

Some key figures that exemplify the shift from stereotype to strength through direct visual activism are; Elizabeth Catlett, Faith Ringgold and Betye Saar..

Elizabeth Catlett’s work addressed cultural belonging and activism, with her pieces often focused on the Black women’s experience. Because of the political themes she explored in her art, the sculptor and printmaker spent much of her career as an expatriate in Mexico City, and her activism led to her investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee in the 1950s

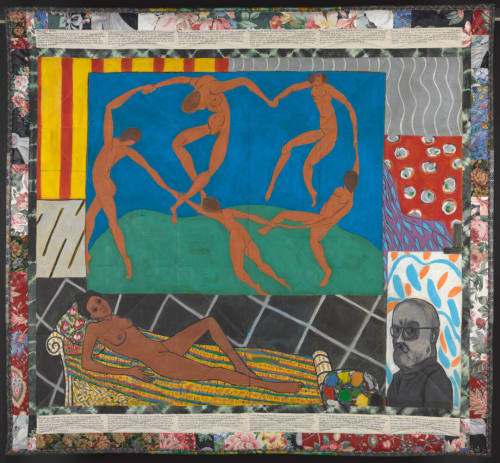

Faith Ringgold is known as a pioneer of the story quilt, using textile, paint, and narrative to elevate Black women’s dreams and struggles. She used her oil paintings to condemn the exclusion of women and people of color from institutions like the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art. Ringgold’s quilts, such as those that reference Manet and Matisse, place the Black odalisque firmly at the center of art history.

Betye Saar funneled her anger, following the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., into art. Her most celebrated piece, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), took the Mammy caricature, long seen as derogatory, and reworked it to be a warrior, a symbol of strength. Radical Black feminist and activist Angela Davis credited this work with “igniting the Black women’s movement” in art

These artists, and others like Howardena Pindell, actively challenged a mainstream art world that still viewed Black female experience as “political” and ignored it in favour of generalized “women” issues. Their efforts ensured that their work, often dealing with themes of racism, sexism, and violence, became central to the Black feminist art movement.

Black Women in the History of Art

This portrait is critical because it captures the complex tension between liberation and objectification during the post-Revolutionary era. Painted six years after France first abolished slavery, the work presents a counter-aesthetic by giving “serious aesthetic treatment” to dark skin. Although the subject’s bared breast has led to interpretations of racialized exoticism, the piece is also read as an “early visual manifestation of intersectionality”, drawing on analogies made by early French feminists between the oppression of “women” and “slaves”. Most importantly, the subject displays “self-assertion” by looking directly at the viewer, and placing her hand modestly over her lower torso, indicating she is “ready to defend and protect her body, her very self from any potential violators”.

I am using Lorrain’s Seaport to illustrate the deliberate historical mechanism of whitewashing and erasure within Western art. Even though the Queen of Sheba was associated with Saba in Ethiopia, the painting depicts her with white skin. This choice reflects a broader trend during the Renaissance where this powerful figure was subjected to “whitewashing and sexualisation on a grand scale”. The persistence of this depiction shows how artists chose to ignore the classical and biblical texts where the Queen of Sheba declares, “I am black and beautiful”. The reasoning behind this alteration appears to be the racist notion that, for many artists, “blackness and beauty… was dichotomous”, making this painting a clear example of the historical visual violence I am investigating.

Depictions of Black Women in Contemporary Art

Ringgold’s story quilt is a foundational work of reclamation that directly challenges the white male gaze in art history. By referencing artists like Manet and Matisse in this textile piece, Ringgold, a pioneer of the story quilt, consciously places the black odalisque “firmly at the center of art history”. Her deliberate move from oil painting to quilting allowed her to “publish her story on her terms”, linking her contemporary narrative practice to the tradition of quilts providing enslaved Black women a “safe space to gather, socialize, and bond”. By using this medium, Ringgold ensures that the Black woman is “finally released from the white male gaze altogether”, making her work foundational for artists seeking to rewrite Black American history and confront injustice.

Thomas’s 2010 piece is an excellent example of the contemporary “seismic correction” that my project is focused on. By reinterpreting Manet’s famous work, Thomas, known for “remixing art history’s most iconic images”, asserts Black authority and self-representation. Her work is characterized by rhinestone-encrusted portraits that actively “celebrate Black femininity, sexuality, and joy”. This approach functions as both a critique of historical misrepresentation and a radical reimagining of visual culture. By centering three Black women in a canonical, often controversial European scene, Thomas actively participates in “redefining the canon in real time” and challenging the institutional gaze.